The long-awaited call to action came early in 1941 after the Battle of Britain had been won and Germany had withdrawn its invasion troops along the French coast.

The battalion left Britain on the Greek ship Nea Hellas on January 10, 1941, for the Middle East, the men’s original destination when the R.M.S. Queen Mary left Sydney nine months earlier. Spirits were high on the voyage to Egypt except for being fed endless meals of salted kippers.

The battalion disembarked in Egypt on March 8, then went on to El Kantara, Gaza and finally Kilo 89, in Palestine. In transit the troops had their first experience of the Egyptian railways system, carriages with hard back seats and concrete floors.

Along the way they saw their first Italian prisoner-of-war cages alongside the railway line, bringing the reality of the war closer. At Kilo 89 the newly-raised D Company brought the battalion to near full strength with 31 officers and 725 other ranks.

The battalion was also informed that 25th Brigade was now a permanent part of 7th Division, where it stayed for the rest of the war. The battalion first occupied positions at Mersa Matruh, on the Libyan frontier, to defend against an expected German attack.

Since 1939 this pleasant little seacoast town, used as a resort since Cleopatra’s days, had been put into a state of bristling defense with massive wire entanglements, anti-tank ditches, trenches and dugouts everywhere. The German attack never came.

Instead of fighting Germans the battalion’s baptism of fire was against Hitler’s allies, the Vichy French, in the invasion of Syria. It was a short, hard-fought, brutal offensive lasting from June 8 and until July 11 when the defeated Vichy French called for a ceasefire and signed an Armistice.

The campaign proved to be much tougher than expected. Intelligence reports had predicted the Vichy French would lay down their arms at the first shots. Instead, they fought stubbornly, and bravely; with many hand-to-hand combats. The conditions were tough. The battalion fought mainly in company groups in mountainous, rocky terrain around Merdjayoun, Ferdisse and Jezzine. Great difficulties were experienced in maintaining supply lines

One of the battalion’s first tasks in the Middle East was to stand ready to defend Tripoli against an expected German attack. Here, members of C Company, in training, man trenches in a section of the defence line.

Anti-aircraft defence was one of the main features in fortifications for the Port of Tripoli. Two members of the 2/33rd Battalion, NX86722 Private C.R. Hollis and NX2756 Private E. Hillier manned this post, which was constructed using sandbags and rocks

Officers at Mersa Matruh: Left to right – VX11954 Captain Kenneth Lawson, Q.M., Lt. Col. R. Bierwirth C.O., QX6011 Major Clement Cummings, 2ic,QX6439 Captain Neville Morgan, R.M.O.

Two members of the Spahi, the French Colonial Cavalry, known as the brown horse squadron because all their horses, with a white blase on the head, were identical. The Spahi were superb horsemen and tough fighters.

Members of C Company loading up a donkey with rations and ammunition ready to be transported to the rest of the company who were in a strategic position overlooking one of the mountain roads to Merdjayoun, near Khiam

Mule trains were brought in to help because of the terrain and the shortage of trucks, but in taking the fight to the enemy the men still had to make many exhausting marches carrying heavy loads of stores and ammunition. They were often short of food and water. Oven-like heat by day and bitter cold nights, with the men wearing only summer uniforms, tested endurance to the limit.

Despite the arduous conditions all companies and platoons quickly built reputations for toughness and skill in combat, infl icting many heavy defeats on the enemy.

As a result, the battalion emerged from the campaign battle-hardened for the days ahead and in a much stronger position than when it started. Not everything went to plan. VX12699 Lieutenant Kevin Power, later Captain, Military Cross winner and one of the heroes of the Kokoda and other campaigns, got himself into trouble with Lieutenant Colonel Bierwirth’s replacement as C.O., QX6152 Lieutenant Colonel R. F. Monaghan, over the purchase of mules.

Monaghan instructed Power to negotiate the purchase from a local village leader who tried to palm off on Power some old, fl ea-bitten animals at exorbitant prices. Power refused to pay.Near the village he saw a string of strong, healthy mules. Their handlers said they weren’t for sale.

Annoyed by the whole affair Power took matters into his own hands. He fired a volley of shots near the feet of the handlers who took off in fright.Lieutenant Colonel Monaghan was delighted when Power returned with a truckload of sturdy mules, until a complaint from the village revealed how Power had acquired them.

Mule trains (top right) were essential for carrying ammunition and rations to the Australians fighting in rugged terrain in Syria. One of C Company’s principal handlers (above) was NX15179 Pt. D.W. Jones. They were also useful “conveyances”, as QX4048 Sgt. Allison “Doc” Trenow(right) shows outside the Gaza Police Station.

He was ordered to give them back.There were other lighter moments, such as the time two soldiers, one a hot-tempered Irishman, got into a fist fight to settle an argument. Beforehand, the Irishman removed his false teeth

and put them on the top of a rock. Just as the fight began the enemy started a new attack with bursts of heavy machine gun fire. A stray bullet hit the luckless soldier’s false teeth smashing them to pieces. He went the rest of the campaign without his dentures.

As in all campaigns, the battlefronts in Syria provided a cavalcade of bravery; ordinary men doing extraordinary things. Men from all ranks responded alike to praise: “ I was just doing my job, and looking after my mates.”

VX11743 Sgt. Ian Dwyer was looking after his mates of 13 platoon C Company when, leading the first patrol on the first day of the Syria campaign, he became the first member of the battalion and the first N.C.O. to be awarded a Military Medal.

Showing no fear, he repeatedly exposed himself to heavy fire to disconnect enemy telephone lines and examine two bridges to make sure they weren’t mined and were safe for his men to cross..

The battalion’s Bren Gun carriers, seen here near the village of Dan, played a vital role in the defeat of the Vichy French.

Sgt. Ian Dwyer, the battalion’s first Military Medal winner.

Lt. Col. Tom Cotton, the battalion C.O. at war’s end, and its most decorated soldier, made his mark early with his award of a Military Cross in Syria as Captain commanding A Company.

His Military Medal also recognised his courage and leadership two weeks later, June 23, during the battle for Little Pimple.

In the same battle QX1352 William Gesch became the first private to win a Military Medal. The victory at Little Pimple, near Ibeles Saki, was the battalion’s most important of the Syria invasion. C Company captured this strategically vital hill from the Vichy French who spent the rest of the day trying to get it back. Throughout the day it was touch-and- go.

The French launched numerous counter attacks with many hand-to-hand melees and grenades being thrown back and forth.

Between attacks the Vichy French constantly shelled and mortared the hill. C Company lost five killed, 16 wounded and six missing who had been taken prisoner.

The Footsoldiers recorded that Sgt Dwyer and Corporal Gesch were at the forefront of the fighting.

Despite falling unconscious for a time with a serious head wound, Gesch played an important part in the victory when he and two others in a trench held off 50 Vichy French trying to flank C Company.

There were three other men in the trench when the battle began. One was killed soon after the start. Gesch and the other two fought off attack-after-attack for hours until the enemy finally gave up and retreated. One of the men to be killed during the battle for Little Pimple was the highly respected Lance Sergeant NX8038 Neil Henderson, aged 30, a grazier from Mungindi, NSW.

Two Military Crosses, the highest decorations for officers after the Victoria Cross, were awarded in other battles. One was to the O.C. of A Company, WX 299 Captain Tom Cotton and the other to WX335 Captain Gordon Bennett, O.C. of B Company. The outstanding leadership they first showed in Syria continued for the rest of the war. Tom Cotton’s success surprised no one. He was fearless in battle and inspired all who served under him, in Syria and every other campaign. He enlisted as a private and rose to become a Lieutenant Colonel as Commanding Officer in New Guinea and Borneo. By war’s end he was the battalion’s most decorated soldier.

The 9 Platoon party that scaled the walls of Fort Khiam: NX44600 Corporal G. A. Campbell, WX96 Sergeant Murray Sweetapple, NX34870 Lieutenant George Connor and NX41301 Private J.J. Wayte.

His Military Cross was a reward for his courage in leading A Company’s successful attack on Fort Khiam, the second most important victory of the campaign. His citation made special reference to him inspiring his company on many occasions in their first experience of severe shell and mortar bombardment, as well as machine gun fire.

NX34870 Lieutenant George Connor was awarded the Russian Order of Patriotic War 1st Class for his heroic actions, in particular his single-handed grenade and light machine gun attack leading to the final capture of Fort Khiam.

WX 96 Sergeant Murray Sweetapple, of 9 Platoon played a prominent part in thecapture of the fort. He and others were with Lieutenant Connor in the final assault. Captain Gordon Bennett won the Military Cross for outstanding bravery and leadership between June 9 and 11 when his B Company, isolated near Khirbe for three days, repulsed repeated cavalry and infantry at attacks, infl icting heavy losses on the enemy.

A Company troops in the courtyard of Fort Khiam. The capture of the fort by men of the 2/33rd Battalion was one of the most significant victories of the Syria campaign.

Captain George Connor, wearing his Patriotic Order of War 1st Class, awarded by the Russians for his gallantry in Syria. Connor was captured during the fighting and spent two months as a prisoner-of-war before being released bt the Vichy French.

Bennett’s B company and its 11 Platoon achieved what William Crooks nominated in The Footsoldiers as the battalion’s two most spectacular victories of the entire war, one at Ferdisse and the other at Rachaya El Fokhar. Both involved an outstanding young officer under Bennett’s command, VX11589 Lieutenant Doug Copp, who won Military Cross during the Lae campaign fighting under his real name, Harry Dugald “Dug” Cullen. Cullen enlisted in the Army in 1938 and was posted to the Darwin Mobile Force. When war broke out he wanted to join the 2nd AIF but his commander refused the transfer.

Doug and a mate, Norm Tinsley, went A.W.O.L. and travelled to Melbourne where they enlisted under assumed names. Cullen chose William Douglas Copp, a relative of his mate. His military

skills soon came to notice. He had been promoted to Staff Sergeant by the time he sailed to England in May, 1940.

In England he was chosen for a short commissioning course and was a second lieutenant by July that year.

His tactical skills played a major part in the Ferdisse victory on June 10 when 150 French infantry approached a position held by Copp’s 11 Platoon, B Company. Always cool under fire, Copp ordered his men to stop firing and instructed one section to stand up to give the impression they were retreating. The rest of the Platoon lay in ambush. Copp gave the order to open fire at close range.

William Crooks wrote in The Footsoldiers: “The whole line of probably 50 men went down like ninepins.” The French immediately withdrew. 11 Platoon suffered no losses. The other spectacular victory was a week later when Gordon Bennett’s B Company, ambushed and inflicted heavy losses on attacking French cavalry near Rachaya El Fokhar. The dramatic scenes are depicted on the dust jacket of The Footsoldiers.

Captain Bennett became one of the battalion’s most influential and gallant officers, serving with great distinction in all four major campaigns, Syria, the Owen Stanleys, Lae-Ramu and Borneo. He was one of the few originals left in the battalion on the Japanese surrender.

Left: Military Cross winner,Captain Dugald Cullen, was one the battalion’s bravest of the brave. He went A.W.O.L. from the Army’s Darwin Force to join the 2nd A.I.F. under an assumed name, Doug Copp. His leadership qualities emerged as a Lieutenant in Syria, especially in the attack on the French Cavalry.

Right: Captain Tom Cotton and Captain Gordon Bennett were awarded the Military Cross for gallantry and outstanding leadership in Syria.

B Company attacking the dismounted French cavalry attacking C Company below Rachaya El Fokhar, Syria, 16 June, 1941. A sketch by Peter Harrigan from details by Captain Bennett and Lieutenants Harrigan, Copp, Dwyer and Marshall.

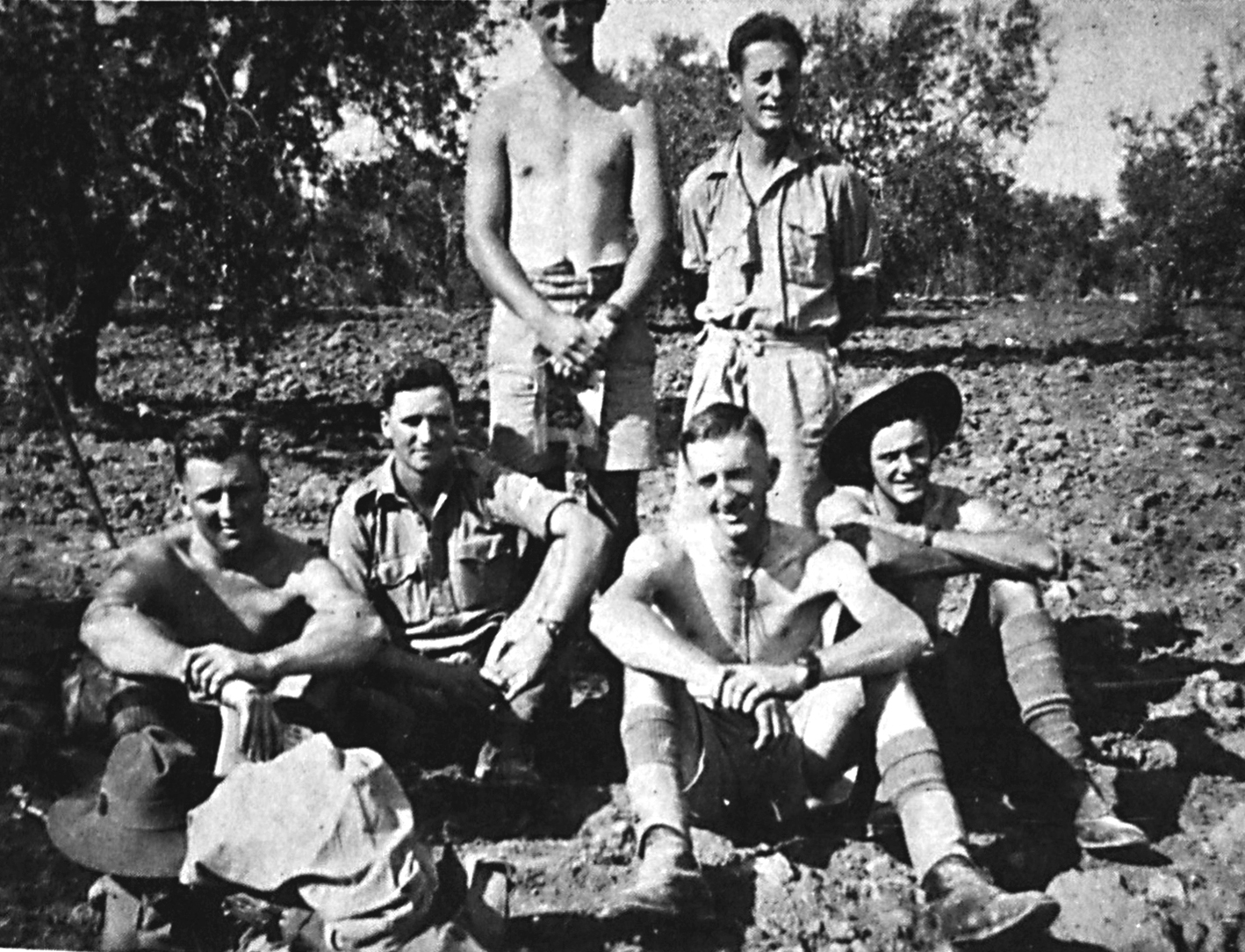

Some of 16 Platoon at Tripoli. Jock Proudfoot, Bruce Stanton, Jack Ferguson, Percy Druhan, Ted Cafe, “Stick” Ellis and Oscar Nagel.

The ceasefire and armistice on July 12 ended the Syria campaign, but the places of famous battles such as Banias, Ferdisse, Hasbaya, Jezzine, Er Rama and Merdjayoun, among others, lived on in the memories of those who took part. Memories also lived on of mates who didn’t make it. Twenty were killed, 84 wounded and 26 captured and taken prisoner.

The last veteran to serve as President of the 2/33rd Battalion Association Battalion Association, NX43720 Private, later Lance Sergeant, Ray Gibson, was one of the reinforcements who joined the battalion at Dimra, Palestine, replacing men killed, wounded or captured during the Syrian campaign.

Some of I7 Platoon at El Fidar, Lebanon, August, 1941. Bert Flaherty, Les Cook, Frank McTaggart, “Slim” Turnbull and Albert “Anzac” Drane.

He well remembers Christmas Day at Dimra: “It rained like hell and our tent blew down right on midnight.” Much controversy surrounded the defeat of the Vichy French.

Neither the battalion nor the 7th Division received the recognition and credit they deserved. News about their victories was censored because of concerns about possible negative public opinion in Australia about fighting soldiers from allied France, even though the Vichy French were renegades fighting for Hitler. The fact the 7th Division’s victories in Syria were “hushed up” was the reason newspapers and troops of other divisions started calling it “The silent 7th”, saying they had no idea where the 7th was fighting or what they were doing.

Japan’s treacherous sneak attack on Pearl Harbour, on December 7,1941, brought the United States of America into World War II.

Two of the battalion’s bandsmen carry one of their most prized possessions, the bass drum, onto the USS Mount Vernon for the voyage home.

British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, who wanted Australia’s 7th and 9th division troops to go to Burma.

Australia’s Prime Minister, John Curtin, defied Churchill by ordering the 7th and 9th divisions home to defend Australia.

The name stuck for the remainder of the war, especially during the Kokoda and the Lae-Ramu Valley campaigns when secrecy about troop movements was paramount. With the Vichy French surrender the battalion undertook garrison duties in Lebanon and Tripoli while awaiting its next deployment. It came as a complete, but worrying surprise. The news hit hard that Japan’s treacherous sneak attack on Pearl Harbour December 7, 1941, had brought the war to Australia’s very doorstep.

The Australian Prime Minister, John Curtin, immediately ordered the 7th and 9th divisions home to defend Australia against the Japanese, defying the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, who wanted the two divisions in Burma to support British and Commonwealth troops.

Right: Men of the 2/33rd Battalion and other 7th Division troops marching to embark at Port Tewfik, Egypt, in February, 1942, for the long voyage home to help save Australia from the Japanese.

There was no ambiguity in Curtin’s curt message to Churchill, saying: “We helped you defend your homeland, now we need to defend ours.”

Apart from that blunt message about where Australian troops were most needed, Curtin was convinced sending our troops to Burma would cost significant casualties for little or no gain.

The American liberty ship USS Mount Vernon brought the 2/33rd Battalion home, leaving Port Tewfik, Egypt, on February 9, 1942, arriving in Adelaide on March 9. They and other 7th Division troops were given a huge welcome home in Adelaide, unlike the week before in Fremantle when the ship docked unnoticed and without fanfare because the locals didn’t know who they were.

The complete lack of a welcome after all their heavy fighting in the Middle East annoyed the troops. They were further annoyed that the locals, who hadn’t been told who they were or where they had been fighting, were giving hero welcomes to thousands of US servicemen on leave. Many brawls broke out as some of the Australians took out their frustrations on the Americans. The confrontations were often referred to as “The Battle of Fremantle”.

SYRIA -LOOKING BACK IN ANGER

A n aftermath of the Syria campaign was a feeling of biterness among many men of the 7th Divison’s 21st Brigade and 25th Brigade, which included the 2/33rd Battalion, for not receiving due recognition for their tough battles to defeat the Vichy French.

The British Government, and a compliant Australian Government, went to extraodinary lengths to deny the brigades the praise they so richly deserved. In the early part of the war other Australian divisions, including the 6th and 9th Divisons were getting all the news headlines for their gallant actions against the Germans in Tobruk and on other fronts, whereas no-one knew where the two 7th Brigades were fighting, leading them to be given the nickname “The Silent 7th” which stayed with them for the rest of the war.

It was upsetting because it gave the impression the 7th Division wasn’t pulling its weight and that others were doing all the serious fighting. But one unfortunate result was that when the ship bringing home men of the 7th Division, including the 2/33rd Battalion, they arrived in Fremantle without the fanfare given to other returning soldiers because no one knew who they were or where they had been fighting. Other divisions and brigades were given welcome home and thank you parades in the major cities, but the 7th Division had to wait until 1944 when it was finally given a victory parade before adoring crowds in Brisbane.

That parade finally gave the 7th Division the recognition it deserved, but there was still much lingering anger by those who had fought and watched mates die under a veil of secrecy in defeating the Vichy French in Syria.

A former war correspondent, the late John Hetherington, who covered the Syria campaign for

The Melbourne Herald, cast new light on the subject when reviewing the first edition of The Footsoldiers in 1971 and recently republished in the Battalion’s newsletter Mud & Blood.

Hetherington wrote: “Footsoldiers don’t forget – they look back in anger, to Syria. Soldiers have long memories. The years slip by and become decades, but the memories of a battalion or a brigade or a division once subjected to misrepresentation – even in a theoretically good cause, aren’t forgotten. Why should they?

The Footsoldiers, which is the Second World War history of the 2/33rd Battalion, looks back in anger to Syria, 1941, and with good reason. The battalion was one of the units of the 7th Division, whose efforts in that gruelling campaign were deliberately elbowed into the shadows to serve the ends of Britain’s wartime propaganda (and Australia’s). The British decided to move into Vichy French Syria in June 1941, to ensure that it would not become an Axis base. Two brigades of the 7th Division (the 3rd was still locked up in besieged Tobruk) formed the bulk of the effective combat forces. The six week campaign, in which the Vichyist defenders disputed every foot of ground was cruel and exhausting, but the soldiers who overcame them received meagre public credit at the time. Post war military historians have corrected the record but the plaudits came rather late.

As a war correspondent in Syria, I remember the censors blue-pencilling practically every hint of the severity of the operations out of the stories that I and other reporters wrote. We were not even allowed to write of Vichy “prisoners”— we had to call them “surrenderees.” It wasn’t the censors’ fault, they were obeying orders designed to discourage the world from supposing that the British were at military death grips with France, which had been Britain’s ally against the Axis until a year earlier. The most astonishing propaganda brain-wave of all came from a certain Major General Sir Edward Spears, head of the British Military Mission to General de Gaulle. He proposed that “while we were advancing the French should be shouted at to get out of the way and let us get at the Germans.” The idea was rumoured to have lapsed when someone suggested that General Spears should lead the way and do the shouting.

All this is old history now, but the 2/33rd and other 7th Division units who served in Syria, and doubtless also the British, Indians and free French who were there, remember it with understandable resentment. Writing of that propaganda policy, Mr Crooks says. “Few at the time were upset by this, but it was the beginning of that playing-down of our efforts that in later years gave rise to the description of us as the “Silent Seventh” and other such remarks that at times got quite ugly in gatherings with men of the 6th and 9th Divisions.”

“Later, when we returned to Australia most people were aware of the activities of the 6th Division in the desert, Greece and Crete and the 9th Division at Tobruk. Few had heard of the prolonged and bitter fighting of the 7th in Syria.”

William Crooks offers some revealing figures.

In Syria the 21st and 25th Brigades had 416 officers and men killed in action and more than 1100 wounded, heavier battle casualties than any Australian formation had suffered in other operations in the Middle East. Not that The Footsoldiers is a querulous book, dwelling on ancient wrongs. On the

contrary, it is a cheerful book, a soldier’s book, rich in a spirit of comradeship, of hardships lightly borne, of high courage. It is massive (528 pages), lavishly illustrated and written with a total absence of literary heroics or verbal frills. In short, it is a testament to the author’s devotion and industry as well as to the feats of a unit which, having distinguished itself in Syria, came home to win honours in the Kokoda Trail operations and the later New Guinea and Borneo campaigns.

Although no exception to the rule that a good battalion history does not make easy, popular reading, it contains passages which now and then bring the detached phrases of the wartime communiques to ringing life. For instance, in the Ramu Valley:

“Scrambling to the top of the steep slope, ‘J.P.’ McLaughlin saw a Jap in a hole his helmet bobbing up and down as he fired bursts from an 1.m.g. which were holding up the advance. Kneeling against the lip of the summit with the Bren cradled in his arms and yelling ‘I’ll get this bastard’, J.P. fired from the hip. Against the skyline he saw the Jap’s helmet bounce six feet in the air with his head still in it.” That captures the very essence of infantry fighting.